Instrument-Induced Errors and Heat Rate

Although there are a number of physical anomalies that degrade heater performance, this section focuses on issues tied in some way to inadequate level control resulting in a below-design final feedwater temperature. The problems can range from something as simple as inaccurate or fluctuating readings across several instruments that leave the “real” level in question to those that justify taking a feedwater heater out of service. Regardless of the severity, the intention is to show the ripple effect that poor feedwater heater level control has on overall boiler and turbine cycle efficiency (increase in net unit or turbine cycle heat rate). Here are two primary sources of instrument-induced errors:

- Drift (mechanical or electronic). Drift is usually associated with aging instrumentation, moving parts, or is intrinsic to the design, such as with torque tube/displacers. With this technology, calibration between shutdowns is often necessary to achieve reasonable accuracy and prevent nuisance deviation alarms between multiple level transmitters. Responsiveness to rapid level changes can also be slow due to dampening effects fundamental to the principle of operation.

- Vulnerable measurement technology. Many measurement technologies are vulnerable to changing process conditions such as shifts in specific gravity and/or the dielectric constant of the media related to variations in process pressures and temperatures. Certain technologies also cannot provide accurate level from startup to operational temperatures without applying external correction factors, or the specified accuracy is only realized at operational temperatures. In general, technologies that fall in this category include differential pressure, magnetostrictive, radio frequency capacitance, and torque tube/displacers.

Lower-than-expected final feedwater temperature occurs when a feedwater heater is taken out of service due to unreliable level input to the control system or when the level is too high or low. If the condition is a result of high feedwater heater level, the operator would note a decrease in feedwater heater temperature rise, a decreasing DCA temperature difference, and an increasing TTD. The inverse is true if feedwater heater levels are too low. In either of the scenarios, risk of damage to hardware increases, heat transfer is impaired, and feedwater to the economizer is not at the required temperature. There are two probable operator responses to a low final feedwater temperature, neither of which is desirable:

- Overfire the boiler to increase temperature (level too high/low or out of service). This action will increase fuel consumption and emissions, as well as increase the gas temperature exiting the furnace. The increased gas temperature will increase the reheat and superheat sprays. Also, the steam flow through the IP and LP stages of the steam turbine will increase (when the heater is out of service), causing flashing and potential damage to the drain cooler section and possibly cause thermal damage to the tubes.

- Open emergency drains to lower level (level too high). This option causes an immediate loss of plant efficiency and can cause damage to hardware if water is inducted into the extraction line. The worst case occurs when the water is inducted back into the steam turbine, causing a possible catastrophic failure. The best case is that the turbine water induction protection (TWIP) trips the unit, shutting the heater down and causing expensive loss of production and other related costs.

Case Studies

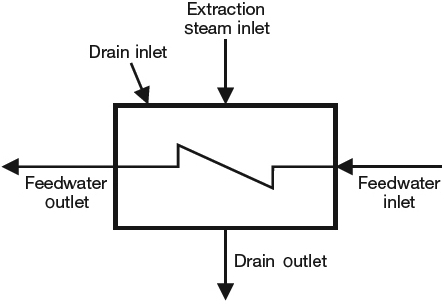

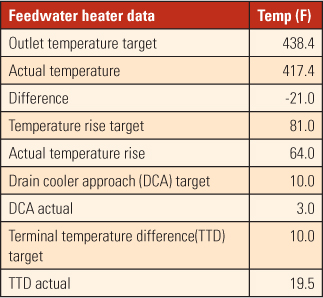

The case studies cover two key topics relative to feedwater heater performance. The first details the increased annual fuel cost associated with an off-design final feedwater heater temperature at a 500-MW coal-fired plant. Although this particular situation does not fall into an extreme case warranting a heater bypass, it exemplifies how seemingly minor trade-offs in level control often have a large impact on unit heat rate (Table 1).

|

| Table 1. Case study 1. This table displays the results of off- design final feedwater heater temperature at a 500-MW coal-fired plant. Based on low outlet temperature, the heat rate rose 47 Btu/kWh, adding $243,000 annually to the plant’s cost of fuel. Source: Magnetrol International |

The second case study brings to light the day-to-day operational risks and costs that ineffective or aging instrumentation technologies have on the bottom line (Table 2). At this plant, the feedwater heaters were replaced in 2002, but the original instrumentation (1966-vintage pneumatic level controls and sight glass) was reused. The unreliable instrumentation caused feedwater heater level fluctuations that intermittently caused a bypass of all the LP heaters as part of the turbine water induction protection and placed the unit at risk of unexpectedly tripping offline.

.jpg) |

| Table 2. Case study 2. Cost justification for replacing aging level controls technology due to excessive bypassing of LP heaters. Source: Magnetrol International |

Note that the case studies do not take into account additional emissions cost, effects on boiler and turbine efficiencies, overfiring conditions, lost production, and other related factors, discussed earlier.

In both case studies, the return on investment for modernizing the instrumentation on the plant’s feedwater heaters fell in the 1.0- to 1.5-year time frame.

—Contributed by Donald Hite, regional manager Southeast Magnetrol International and Orion Instruments. View the POWER webinar on this topic on demand at powermag.com/webinars.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)