An intrinsically motivated safety culture does not usually emerge fully formed. Decisions and actions affecting behaviors are often linked to entrenched attitudes and beliefs within companies. Commitment and accountability are required throughout the organization to recognize, challenge, and resolve issues, thereby providing true safety benefits to work groups.

Accurate workforce performance measurement requires reliable, quantifiable, and reproducible performance indicators. Often, the indicators can be divided into historical (lagging) or predictive (leading) metrics that provide a snapshot of performance at a given point in time.

Accidents, or system failures, which can appear technical in nature, often result from an accumulation of “weak signals.” Performance indicators might not even recognize those weak signals, if the immediate consequences are not serious. However, the inability to take action because of too much information, or lack thereof, can yield major accidents or system failures.

Simply adding more safety devices, a standard response to an unanticipated failure, may paradoxically reduce safety margins by adding system complexity. That fact means abandoning a program may not be justified, but instead, suggests focus should be shifted to the organization and its employees.

From Organizational Culture to Safety Culture

Scrutiny increases dramatically after a disastrous event, which can flesh out some important lessons learned. Using the Fukushima accident as an instructive example, the principal causes that contributed to the severity of the event, as identified by an independent investigation commission, were organizational culture and regulatory systems that supported faulty rationales for decisions and actions. The commission said an insular group mindset had developed at the site, which resulted in the larger-than-projected tsunami’s significance being minimized, allowing flooding and a station blackout to disable reactor-cooling functions, leading to disaster.

Organizational culture is considered to be the shared perception of the organization, including traditions, values, and socialization processes that endure over time. Various models have been developed to explain the phenomenon. One example is known as Schein’s model. It divides organizational culture into three layers—innermost, middle, and outermost.

The innermost layer represents the core component of culture, which is invisible and effectively unconscious. It is inferred from espoused values (middle layer) and artifacts (outermost layer). The artifacts are visible and easily measured, but they can still be hard to interpret without digging below the surface to uncover why a group behaves a certain way.

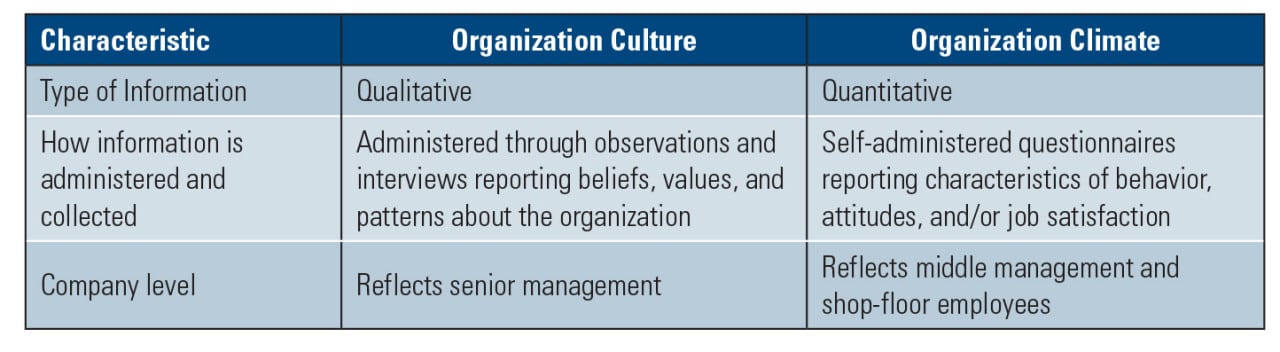

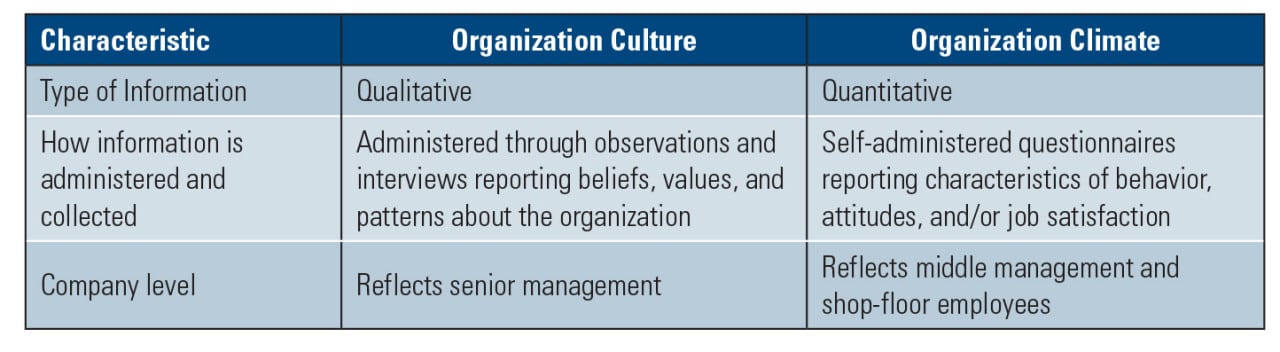

Organizational climate is used to measure selected employee perceptions and characteristics of their environment, that is, an overt manifestation of culture within an organization. These abstract concepts—that climate is culture in the making and organizational culture expresses itself through organizational climate—are often used interchangeably and risk becoming virtually meaningless unless properly defined (Table 1).

|

| Table 1. Culture versus climate. In his article “The nature of safety culture: a review of theory and research” published in Safety Science, F.W. Guldenmund suggests that there are several characteristic differences between organizational culture and climate. Source: F.W. Guldenmund |

Organizational culture and climate, specifically applied to safety, form subsets referred to as safety culture and safety climate, respectively. These are common constructs to discuss safety events (see sidebar).

| Safety Conscious Work Environment, Chilling Effect/Chilled Work Environment, and Reporting Concerns

Some common terms used to evaluate workforce conditions, particularly in the nuclear industry, include: safety conscious work environment (SCWE) and chilling effect/chilled work environment. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) addressed SCWE by issuing a policy statement titled “Freedom of Employees in the Nuclear Industry To Raise Safety Concerns Without Fear of Retaliation” (61 FR 24336) in May 1996. NRC Regulatory Issue Summary 2005-18 “Guidance for Establishing and Maintaining a Safety Conscious Work Environment” followed it in August 2005.

The 2005 publication defined a SCWE as an environment in which “employees feel free to raise safety concerns, both to their management and to the NRC, without fear of retaliation.” Although 2005-18 stated that SCWE and safety culture are distinct concepts, the employees’ willingness to identify safety concerns is an important attribute of a strong safety culture.

Furthermore, if there is a perception that the raising of safety concerns is being suppressed or discouraged, the occurrence is described as a “chilling effect.” If the occurrence has created a work environment where the willingness of a group of employees, or the entire facility, is inhibited, it is referred to as a “chilled work environment.”

NUREG/BR-0240 “Reporting Safety Concerns to the NRC” describes how concerns are received, evaluated, and closed by the NRC.

|

Safety culture and climate have been extensively researched creating numerous definitions, theories, and models, some of which even conflict. The diversity of the conclusions results from the variable ways in which safety culture and climate can be framed and studied. Although no single definition, theory, or model has been universally accepted; many of them discuss tentative relationships following layered models.

Safety Culture Goes Nuclear

The term “safety culture” as part of the nuclear lexicon can be traced back to the Chernobyl-4 graphite-moderated nuclear reactor post-accident review in 1986. An autopsy of the accident—a steam explosion and fire that released radioactive reactor core fragments and fission products into the atmosphere—determined that the event was caused by the concurrence of rector physical characteristics; control element design features; an unauthorized state not specified by procedures or investigated by an independent safety body; and communication inadequacies between operators and regulators, coupled with a lack of clear lines of responsibility.

The International Nuclear Safety Advisory Group, an advisory group to the Director General of the International Atomic Energy Agency, was tasked with investigating the accident. It found, “The vital conclusion drawn is the importance of placing complete authority and responsibility for the safety of the plant on a senior member of the operational staff of the plant. Formal procedures properly reviewed and approved must be supplemented by the creation and maintenance of a ‘nuclear safety culture.’ This is a reinforcement process which should be used in conjunction with the necessary disciplinary measures.”

The Chernobyl accident demonstrated that lessons learned from the Three Mile Island (TMI) accident in 1979 had not been implemented. Following TMI, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and U.S. nuclear industry, under the heading of human factors, focused on improving operator qualifications and training, staffing levels and working conditions, man-machine interfaces, emergency operating procedures, and organizational/management effectiveness. Although not labeled “safety culture” at the time, the TMI investigation report concluded that the principal deficiencies in commercial reactor safety were not hardware problems, but management problems.

In the late 1990s, the NRC incorporated “risk-informed” elements into its oversight process. The NRC defines risk-informed as an approach where risk insights, engineering analysis and judgment, and performance history are used to align activities with areas posing greater risk. That decision led to the NRC’s reactor oversight process (ROP) replacing the systematic assessment of licensee performance (SALP) evaluations that had been held less frequently.

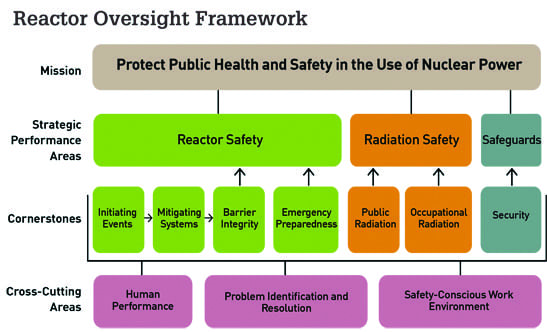

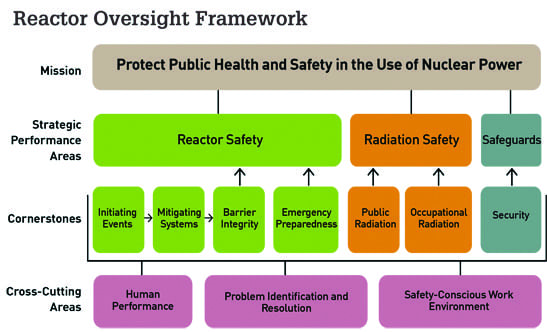

The ROP makes use of both inspection information and monitored performance indicators to identify widespread issues rather than just isolated incidents, and it encourages licensees to take action before significant performance degradation occurs. Crosscutting areas, such as human performance, problem identification and resolution, and safety-conscious work environment are considered conceptually related to safety culture. The framework supports seven “cornerstones” reflecting essential safety and safeguard aspects of facility operation (Figure 1).

|

| 1. Reactor oversight framework. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s (NRC’s) mission is to protect public heath and safety in the use of nuclear power. The framework shown here is used to help it meet that objective. Source: NRC |

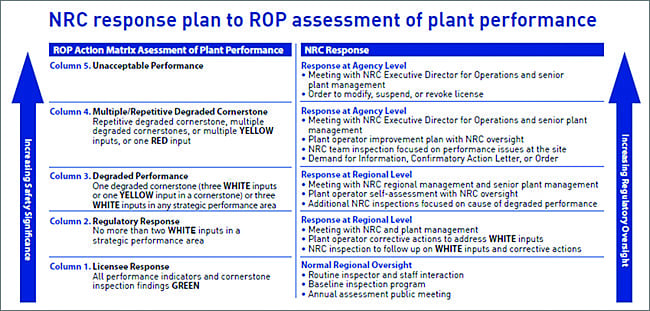

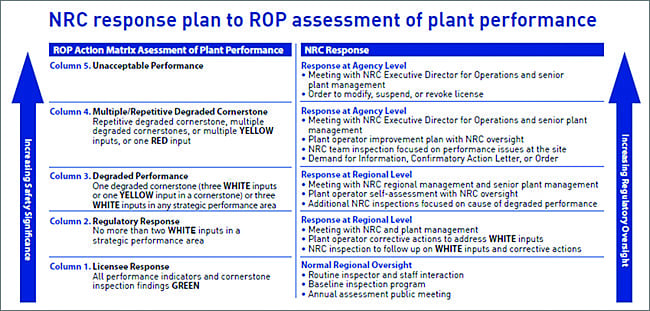

The ROP action matrix has five columns of increasing oversight. Individual plants are organized in the matrix based on their effectiveness in meeting objectives measured quarterly by performance indicators and inspection findings. Findings are color-coded using green, white, yellow, or red in increasing significance (Figure 2).

|

| 2. Facilities are risk-categorized using color-coded indicators. Under the reactor oversight process (ROP), the NRC links regulatory actions to performance criteria. The process uses five levels of response with NRC regulatory review increasing as plant performance declines. Source: NRC |

Licensees in column one are subject to the NRC’s baseline inspection program. As licensees move to higher columns, they are subject to supplemental inspections focusing on areas of declining performance including regulatory actions ranging from management meetings up to and including orders for plant shutdown.

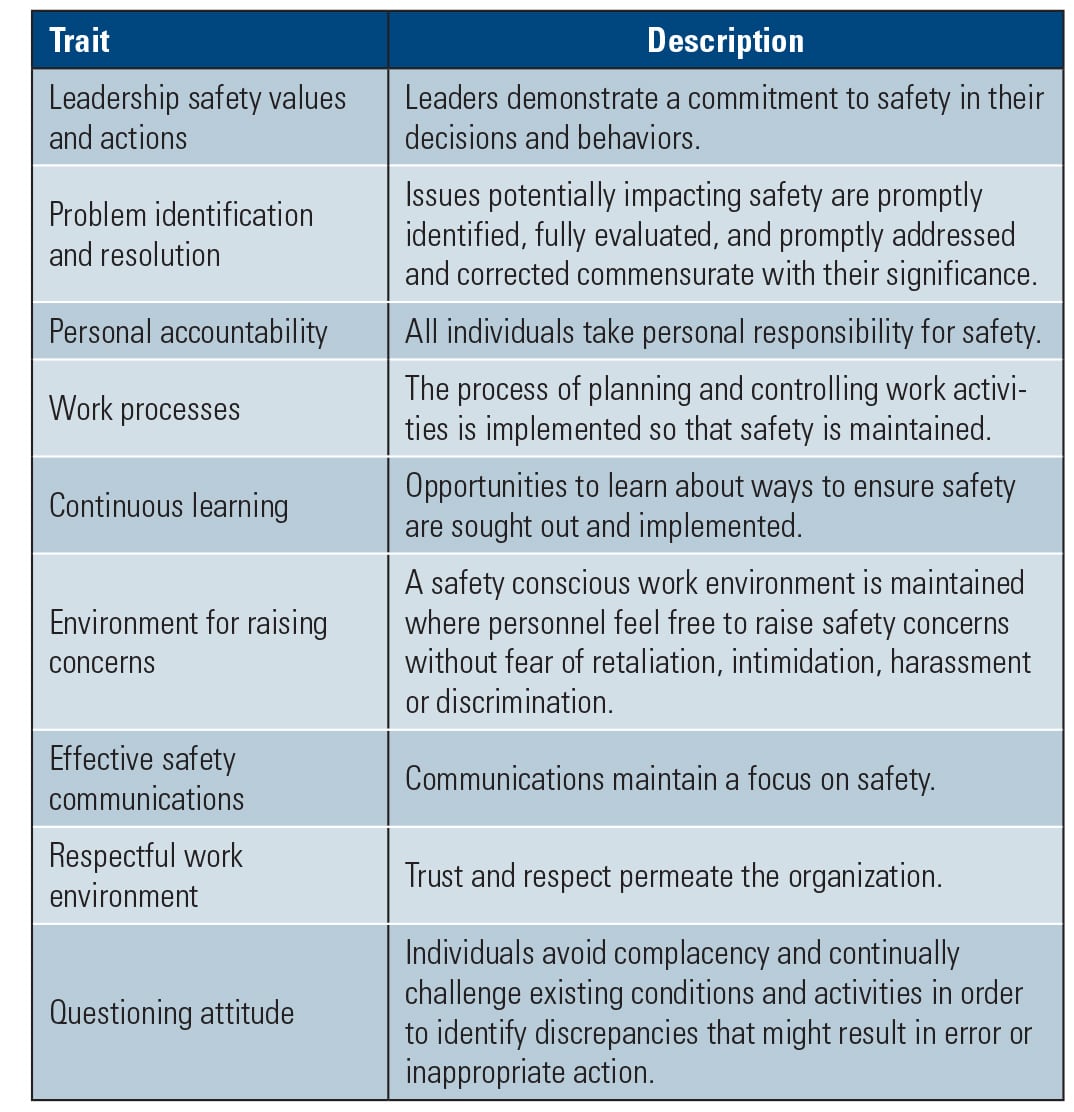

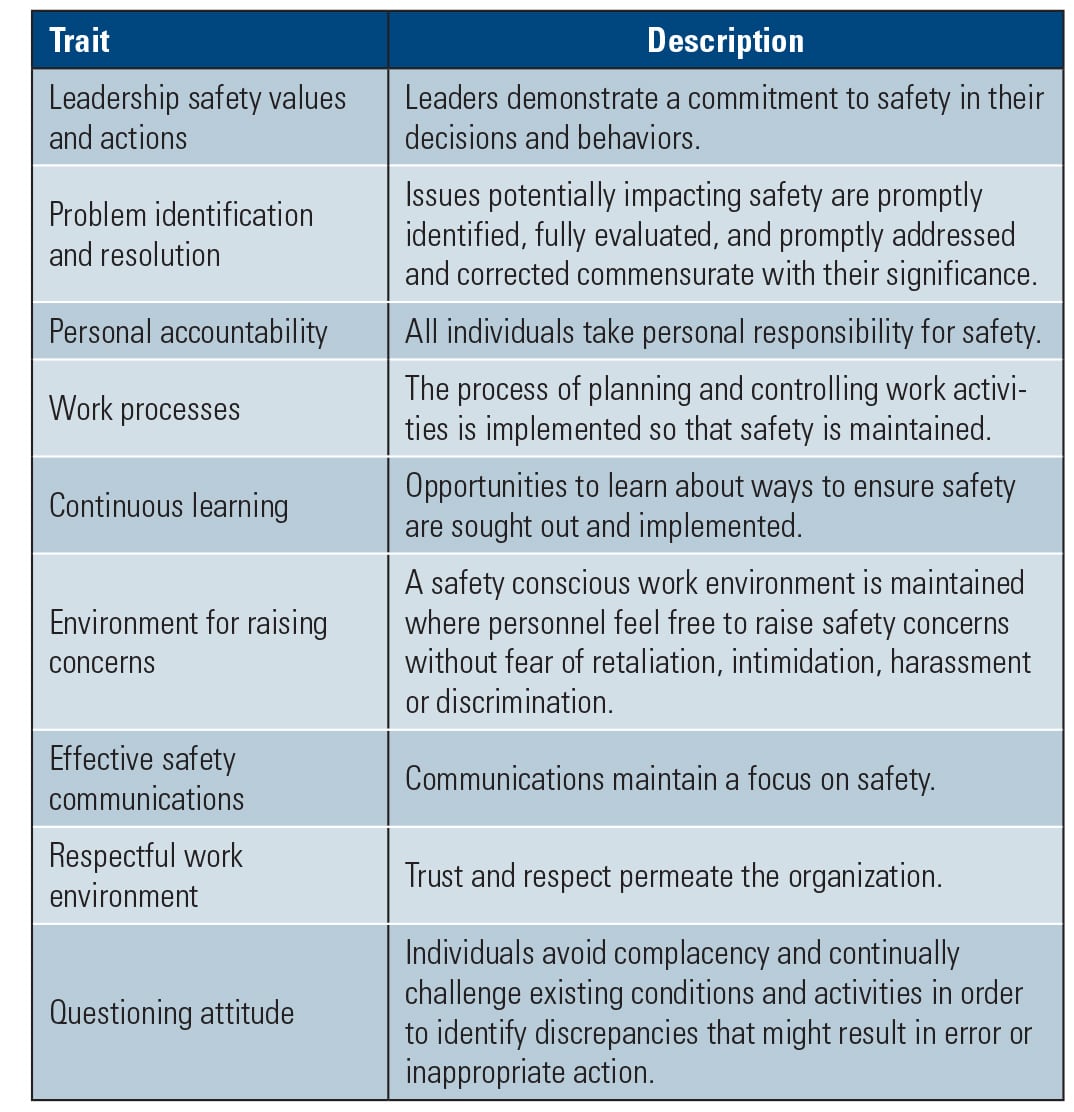

The NRC published its definition of a nuclear safety culture in 2011. It said, “The core values and behaviors resulting from a collective commitment by leaders and individuals to emphasize safety over competing goals to ensure protection of people and the environment.” It included nine traits important to a healthy safety culture (Table 2). Stakeholder feedback later identified an additional trait—decision-making—to be of equal importance to the NRC-identified items.

|

| Table 2. Traits of a healthy safety culture. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) identified the nine items shown in this table as important traits for developing a positive safety culture. Source: NRC |

Assessing Safety Culture

Safety culture is distinct from compliance-based control. To explore the relationship between safety culture and performance indicators, the NRC conducted a survey in 2010 involving 97% of the operating U.S. nuclear plants. General results of the survey, as reported in the article “Exploring the relationship between safety culture and safety performance in U.S. nuclear power operations” published by Safety Science in November 2014, included the following:

■ Organizations where employees perceived less of a questioning attitude were more likely to receive higher numbers of allegations. When employees are more likely to report safety concerns through the allegation program, it may be an indicator that they have less confidence in their internal processes for identifying and resolving safety issues.

■ Fostering a questioning attitude may be a particularly important component of the overall safety culture of an organization.

■ Organizations with lower overall scores were more likely to have higher counts of unplanned scrams, and have inspection findings related to inadequacies in problem identification and resolution.

■ The correlation between safety culture and unplanned scrams seemed to be driven by training quality; and the correlation with problem identification and resolution was related to management’s commitment to safety.

■ Sites with lower scores were likely to receive substantive crosscutting issues, and to be in an elevated oversight condition within the ROP action matrix the following year. Lower scores may indicate problems that are starting to add up, and it is only at future points in time that those problems, if not adequately addressed, require NRC response and movement in the ROP action matrix.

■ The only safety performance measure not significantly correlated with safety culture was the industrial safety accident rate. Accident rates are one of the most commonly used independent measures of safety performance. However, many have noted concerns with using accident rates to represent performance, primarily that accidents may be few and far between and do not capture the frequency of microevents, that is, weak signals, such as near misses or minor incidents that do not meet accident reporting requirements. The industrial safety accident rate seems to be a less-relevant measure of performance to an organization’s safety culture.

There are no established thresholds for determining whether a safety culture is “healthy” or “unhealthy.” However, there are factors mentioned throughout safety literature that contribute to a positive safety culture. Such factors include:

■ Senior management commitment to safety over production

■ Participative management leadership style

■ Shared values and contributions among all organizational levels

■ Multilevel communication to elicit varied viewpoints

■ Regulatory-driven and conservative practices for mitigating defined and undefined hazards