In the information technology world, open-source platforms and software, as an alternative to proprietary ones, have long been commonly accepted. In process controls, not so much. That could be changing if some large customers have their way.

For decades, the norm with industrial plant distributed control systems (DCS) has been that you buy a proprietary process control system from a vendor and are then locked into that system for 20 years or more. The vendor may roll out upgrades over time, but eventually, either the vendor ends support, rendering the system obsolete, or the advantages of new system capabilities argue in favor of ripping out the entire system and replacing it—with another proprietary system.

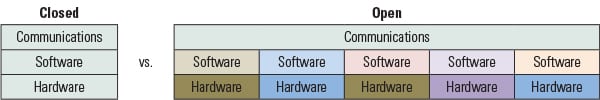

Recently, two large industrial companies made waves when they called for a change in that model. As reported in a February 19 story at Automationworld.com, ExxonMobil and Lockheed Martin want to create an “open and secure automation system for process industries” to “ensure modularity, interoperability, extensibility, reuse, portability, and scalability” (Figure 1).

|

|

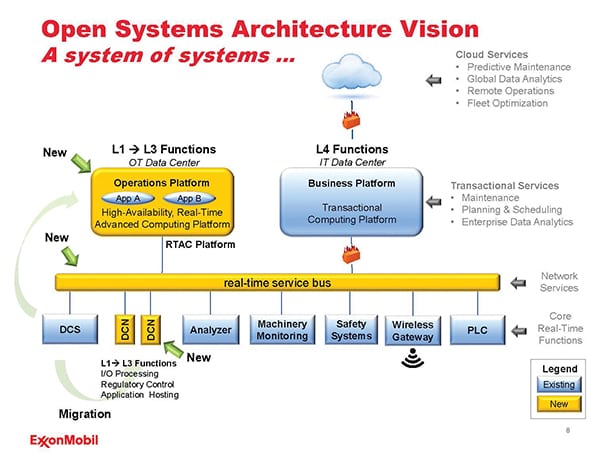

1. Automation: The next generation. This graphic, released at the 2016 ARC Forum, depicts ExxonMobil’s vision of the next evolution of digital industrial systems. Courtesy: ExxonMobil |

That’s the technical rationale. The economic rationale is to reduce capital costs and accelerate project schedules.

A January 14 press release announced that “ExxonMobil Research and Engineering Company (EMRE) has awarded Lockheed Martin a contract to serve as the systems integrator in the early stage development of a next-generation open and secure automation system for process industries. Lockheed Martin will be responsible for the advanced processing architecture working with EMRE in this pre-development phase.” In that release, Vijay Swarup, EMRE vice president of research and development, was quoted as saying, “This breakthrough initiative could help transform refining and chemical manufacturing through the use of high-speed computational components, modular software, open standards, and the use of autonomous tools.”

The power industry, too, is always looking for ways to cut capital costs and execute technology changes faster while gaining flexibility. Could open controls be coming to the power industry as well? Even though traditional power generators are famously conservative when it comes to adopting new technologies, if the industrial control system (ICS) world moves to the type of environment envisioned by ExxonMobil and Lockheed Martin, it’s just a matter of time until the same capability becomes available at power plants.

Open vs. Proprietary Control Systems

Open-source systems are those for which the source code or design is publicly available and can be used, modified, and shared by anyone (though there are often restricitions in the specifics, for example, derivative versions typically must also be open-source). It enables collaborative, transparent development and modification—typically much faster than when working with proprietary systems. It is also, its advocates argue, a way of thinking that is more, well, open and collaborative—more like social media than mass media.

Open-source is also now mainstream. If you’ve used the Linux operating system or the Firefox web browser, you’ve used open-source systems, whether or not you were aware of it. Microsoft Windows and Adobe Photoshop, by contrast, are examples of closed systems. In the information technology (IT) world, the lines between proprietary systems and open-source ones have begun to blur, according to some industry experts. Even historically closed enterprises like Oracle now have their own open-source initiatives.

Two years ago, in a February 2014 post, Eren Niazi, founder of Open Source Storage, argued that “The open source versus proprietary contest is ending because a critical mass of technologists in business and government recognize that open source technology offers higher performance, scalability, and reliability at a much lower price than proprietary solutions.”

Will that notion appeal to power generators? Perhaps—if open-source controls enable a sort of mix-and-match system that facilitates purchasing different-yet-compatible parts from different vendors at different times. However, achieving success in that brave new world would require purchasers and plant operators who are sufficiently sophisticated to make wise decisions. That could be a challenge.

I had the opportunity to talk with representatives of some ICS providers at IHS CERAWeek a week after the Automationworld.com article came out, and I asked them what they thought the implications of a new open controls system might be for them and for the power industry. After that event I asked a few other control system vendors about this idea, and they responded via email. Honeywell declined to comment.

Schneider Electric

In the Automationworld.com story, Schneider Electric’s Gary Freburger, president, process automation, industry business, was quoted as saying, “We have a good majority of the technology and products needed [for an open control system],” but, he added, “The question is around the implications from a business perspective, because it’s not just a technology discussion.”

“Specifically,” the article explained, “it means changing the business model that ICS vendors have adhered to over the years, which includes engagement over the lifetime of the system from maintenance and support to upgrades. This is a model upon which ICS suppliers have generated revenue after the initial system installation.

“Now, manufacturers like ExxonMobil are asking for a lower long-term cost of ownership and the flexibility of working with multiple vendors in order to plug in interchangeable hardware.”

When I asked Freburger about this at IHS CERAWeek, he said that ExxonMobil had standardized on Honeywell controls in the 1980s in its downstream applications, and the system is going to be obsolete soon, so the oil company is looking for a more open structure with separate software, hardware, and connectivity systems—rather than the fully integrated systems currently available from multiple vendors. “Theoretically,” he said, “they could mix and match any of them” (Figure 2).

Philosophically, Freburger said, his company agrees with the direction in which ExxonMobil is headed, but “it’s not clear if it’s completely viable, because it’s a pretty significant change in the industry.” Schneider has been working with the oil company over the past three years, looking at how to replace the existing systems. Freburger thinks that ExxonMobil will move to an open system, where the majority of the control work will be done at the device level, with the assistance of lots of sensors.

“Potentially, that’s the way the market will go,” he said, and Schneider is working with the two companies to help them “prove out that process, which they’re targeting for the end of this year.” If the open approach proves out with ExxonMobil, “It absolutely could work in power as well.”

“The one issue,” he added, concerns cybersecurity. “First and foremost, whatever system we develop has to be safe and secure.” The more devices you connect, the more data you have. Schneider’s view is that you’d keep control system data internally within a facility, and it will never go outside. But as you have more data and the ability to do analytics, there will be more options for where to move and handle the data.

He noted that the Lockheed Martin announcement highlights the fact that one goal is to make the system itself more secure. One school of thought says you can secure the system at the device and software levels. Another says you’re also opening your system up to more opportunities for unauthorized connection and cybersecurity concerns as the number of connection points increase.

An alternative to an open ecosystem, Freburger suggested, is to “future-proof” a system, as he said Schneider Electric is alone in doing with its system (formerly known as Invensys before its acquisition by Schneider Electric). Schneider Electric guarantees customers that when they install a new system, they will always have an upgrade path so they won’t have to “rip and replace” as systems become obsolete. The company also ensures that the new product will work with the old product.

Emerson Process Management

When I asked Emerson Process Management President Robert L. Yeager about the ExxonMobil–Lockheed Martin initiative, he responded, “I think it’s complicated, and there are some things that are very, very difficult and very hard. Having the I/O [input/output] be kind of independent and having some kind of standard interface to it, like you would have some kind of protocol that every vendor could interface every other vendor’s I/O—you can do that. The issue is how fast can you do it, because if you’re in a power plant, especially if you’re doing turbine control, you’re doing a closed-loop, real-time, high-speed control. It’s not the controller that’s the limiting factor, it’s the bandwidth or cycle time of the I/O. So, you have to be careful there, but you can do that…. We could have our I/O interface to Honeywell’s.”

The real concern, he continued, is of a different nature. “One of the things [ExxonMobil and Lockheed Martin] want to do is run software, like off-the-shelf software—even write their own software at the controller level. Everyone’s controller right now runs sometimes 5- to 10-millisecond loops, right? Very high speed. It’s very robust, it’s been vetted out for many years, the software’s very mature at the controller level. If you just kind of let people throw third-party software in at that level, it creates a lot of problems, because if it’s instable, it hasn’t been tested thoroughly, and you’re running that at 10-millisecond loop times, and it crashes, guess what’s going to happen? The turbine or the combustion process the controller is [running]—even if they’re redundant—they trip, the plant trips. You’ve got to be very careful, and it’s not just power, it’s everything.”

There are some advancements in operating system technology, he continued, “where something called page faults” can “kind of isolate certain programs to run at a certain boundary condition. If they crash, they crash within that page fault. They’re not going to go and corrupt the rest of the controller, but it’s still risky. So once you try to get to that level, it becomes very difficult to have multiple vendors putting software in other people’s high-speed controllers.”

At that point, I said, “The bottom line here sounds like you’re not real keen on the idea.”

Yeager responded, “No. Look, we’re not really for or against it, because the market determines what it is. We think for example—we have CHARMs I/O, which is great I/O, and it’s this channel-per-channel I/O (Figure 3). It’s great because you can wait until the last minute to change the database. You might have even heard about this before, but it’s a huge advantage for Emerson and for customers. That might be something where you could open that up as a standard, and it would work with any control system. I think Exxon would love that. The industry would love that.”

At that point, Alan J. Novak, director, mining and power industries, added, “ExxonMobil’s got some really smart people. Lockheed Martin obviously has some really smart people. But there are some unique features in each of the industries we deal with, so we see things in power we don’t see in oil and gas. The risk is when you have an ExxonMobil designing it, it’s probably going to be very specific to [their type of business]. You really have to look at the applicability across industries, because I think it would be very difficult to build a truly generic” system.

Yeager agreed, noting that there are elements specific to the power industry like “valve positioning, speed center, high-speed turbine logic—that kind of thing would all have to be dealt with on a case-by-case basis, but we’re not for or against it. We’ve just got to understand it.”

ABB

Dr. Bernhard Eschermann, head of technology for ABB Process Automation Division in Zurich, responded to POWER’ s questions via email. His comments have been edited for length and style.

How does your company feel about this open controls system concept for power generation and why? ExxonMobil’s concept is in line with the natural evolution that has been taking place in control system architecture over the past two decades—more open, more standards, more interoperability.

DCS systems have evolved, becoming less monolithic and getting more open/standard interfaces for some time already, also in the power generation market. An example of a standard, open architecture is IEC 61850, which is widely used for the integration of electrical devices from different vendors and the standardization of how distributed automation functions need to work together.

The evolution has different speeds in different application areas, but it will continue for power generation as well.

ABB has been a technology leader in this area while continuing to preserve our customer’s investments in their intellectual property (control applications) through our evolution without obsolescence commitment (for example, Symphony Plus, see Figure 4).

https://www.powermag.com/open-system-controls-coming-power-plants/?pagenum=6